Black Bottom was a predominantly Black neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan. The name Black Bottom actually came from the area’s rich, dark soil farmed by French settlers in the eighteenth century, not the African-American population that settled there during the Great Migration. It was located on Detroit’s near east side, within Gratiot Avenue, Brush Street, the Detroit River, and the Grand Trunk railroad tracks. In the early 1900s, many African Americans migrated north to Detroit seeking employment in the city’s growing industries. Racially discriminative housing covenants and redlining forced most of them to settle in Black Bottom, altering the connotation of the district’s name, Black Bottom. As thousands of blacks streamed into Black Bottom, the community swelled with vibrant cultural, educational and social amenities.

The district reached its social, cultural and political peak in 1920. Blacks owned 350 businesses in Detroit, most within Black Bottom. The community additionally boasted 17 physicians, 22 lawyers, 22 barbershops, 13 dentists, 12 cartage agencies, 11 tailors, 10 restaurants, 10 real estate dealers, 8 grocers, 6 drugstores, 5 undertakers, 4 employment agencies, and 1 candy maker.

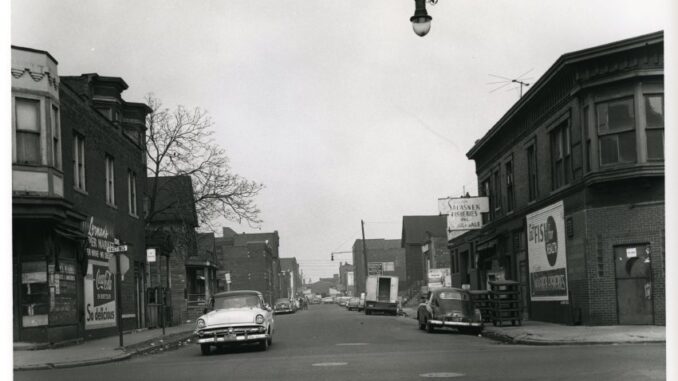

As Black Bottom grew, it soon became known as a lively area with jazz bars and nightclubs. From the 1930s to the 1950s, residents in Black Bottom made significant contributions to American music, including blues, Big Band, and jazz. Famous artists such as Billie Holiday, Sam Cooke, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, and Count Basie regularly performed.

Notable people to live in Black bottom were former Detroit mayor Coleman Young, whose father, William Coleman Young, operated a dry cleaning and tailoring business and also worked as a clerk for the U.S. Postal Service. Others include actress and recording artist Della Reese, and Ralph Bunche, the first African American to earn a Nobel Peace Prize.

Towards the end of the decade, black employment in Detroit dropped by almost 30%. The stock market crash in 1929 only exacerbated the dire circumstances of Black Bottom’s working-class families.

The number of blacks moving into the district continued to increase with the promise of available industrial jobs. Increased demand for housing in Black Bottom allowed landlords to charge exorbitant rents for units in extreme disrepair. For this reason, some households held 3 or 4 families. This also prompted many tenants to take in borders, further increasing crowding and the degradation of living conditions in the district.

Although condemnation of property began in 1946, the National Housing Act of 1949, then later the 1956 National Highway Act, gave the city the funds to begin an urban renewal project in earnest, replacing Black Bottom and Paradise Valley with the Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park, a mixed-income development. The east side neighborhood was gone by 1954 though its entertainment district, Paradise Valley, survived a few years more. Relocation assistance was minimal and many former Black Bottom and Paradise Valley residents were given 30 days notice to vacate. A number of the residents relocated to large public housing projects such as the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects Homes and Jeffries Homes.

Black Bottom was demolished for redevelopment in the late 1950s to early 1960s and replaced with what is now Lafayette Park residential district and the 375 freeway. Written By: Jacinta Chevon